If states were airlines, New York and California would be Delta and United. Even when competently managed, they must shoulder the institutional inheritance of decades of other people’s decisions, good and bad. They must bear the heavy cost of legions of retired government workers. And they carry billions of dollars of debt that backs expensive, complex infrastructure.

Over the last few decades, when New Yorkers and Californians tired of paying high taxes to fund big government, they tended to migrate to what we might call the JetBlue states: Arizona, Florida, and Nevada. In those three low-tax refuges, the construction industry swelled to build houses for the new residents. And the construction workers themselves needed houses, providing jobs for still more construction workers. All the new people needed new places to shop, as well as new doctors, dentists, and restaurants. The local financial industry also grew and grew, filling office parks with the folks who did the back-office work for all the mortgages that New York bankers were eagerly approving. The result: double-digit population growth.

But during the boom times, elected officials in Arizona, Florida, and Nevada took a page out of the old states’ playbook, driving up spending at an unsustainable pace. Now that the growth of the low-tax states has hit a wall, shattering revenues, they face a tough choice: they can raise taxes to fund permanently higher costs, or they can aggressively cut spending. So far, it’s proving surprisingly easy for them to choose Option One, taking a small step toward transforming themselves into the high-tax states that so many of their own residents have fled.

Between 2000 and 2008, the population of the United States grew 8 percent. But Nevada’s population grew nearly four times as fast, Arizona’s more than three times as fast, and Florida’s nearly twice as fast. In 2006, as the housing bubble expanded to its maximum, the JetBlue states boasted five of the nation’s ten fastest-growing cities. Midsize towns sprang from almost nothing—like Queen Creek, Arizona, an hour from Phoenix. In 2000, it was horse and farm country; since then, it has more than quintupled in size, to a humming municipality of nearly 25,000.

Residential property values soared during the same period, more than doubling in Phoenix and Las Vegas and rising even faster in Miami and Tampa, according to Standard & Poor’s. Only Southern California and Washington, D.C., clocked better (though illusory) results. Bubble-era property values mattered acutely to these states’ economies because they helped fire economic growth. As home prices went up, local homeowners, flush with cash from refinancing their houses, dined out frequently and spent lots of money on consumer goods. These tourist-magnet states also drew hordes of visitors from the rest of the country, with their own fistfuls of cash drawn from inflated assets back home, ready to spend and spend.

In fact, all three states are heavily dependent on sales and other taxes paid by tourists. Nevada, for example, derives nearly 60 percent of its general-fund revenues from sales taxes and gaming taxes, and it has long solicited out-of-staters to do the high-rolling spending. “Nevada’s revenue is almost single-sourced,” a spokesman for MGM Mirage told a local TV station earlier this year. “The overwhelming majority is coming from the tourism sector.” The three states are also heavily dependent on the convention business—itself largely driven by a booming financial industry. And all three proved attractive for buyers of second homes—who, confident in the ever-rising value of their good investments, also spent well while on their semipermanent vacations.

Then came the nation’s housing bust, and the states whose property values had accelerated the fastest took the heaviest damage. In Arizona today, a just-opened Wal-Mart and Target sit near acres of dead orange trees, an orchard gone into foreclosure and now drearily neglected. In one of the wealthy, half-decade-old subdivisions that blossomed in the Arizona desert, a house is either for sale or for rent on nearly every block. If its front lawn wasn’t originally “xeriscaped”—that is, planted with natural desert brush that doesn’t require much water—it is now, as the desert has inexorably reclaimed any other greenery.

Invisible on each street are the millions of dollars in mortgage debt now backed by nothing as home values have deflated. A third of Arizona’s mortgage borrowers are now “under water,” according to the real-estate research group First American CoreLogic—meaning that they owe more money on their mortgages than their houses are currently worth. Florida is in similar straits. And in Nevada, almost half of all homeowners have such “negative equity,” including 55 percent of homeowners in Clark County, which includes Las Vegas.

Unemployment in the JetBlue states has also shot up. In just months, all three have hemorrhaged more than half of the new jobs that they had created since 2000 in the high-growth industries of construction, financial services, and tourism. People who aren’t buying new houses don’t need construction workers or bankers to arrange new mortgages. Visitors who aren’t coming—either because they can no longer spend money drawn from ever-rising home values, or because the bailed-out banks they work for are canceling their resort meetings—don’t need new casinos, restaurants, and hotels. Indeed, job losses in these three states have led the rest of the country. Since the economy’s peak in December 2007, unemployment has risen 55 percent nationwide. In Nevada, it’s up 81 percent; in Florida, 79 percent; and in Arizona, 63 percent.

And the three states’ scorching population growth, which stoked so much construction and other economic activity, has abruptly slowed. Partly that’s because people can’t sell their houses elsewhere to buy cheaper houses in the high-growth states; also, people can no longer buy second homes as casually as they could three years ago. In the year leading up to July 2008, says Brookings Institution demographic expert William H. Frey, “compared with their mid-decade peaks, Phoenix took in only half as many migrants, Las Vegas almost two thirds less, and Tampa and Orlando fewer than at any time in almost 20 years.”

As property values and jobs have vaporized, taking tax revenues with them, a trend—not surprising when you look at the old states’ history—has come to light: spending in the three Sunbelt states is way, way higher than it was before the boom started. New Yorkers and Californians are used to their governments’ incorrigibly spending beyond their means during the good times, necessitating ever-higher taxes to fund the higher budget base when the bad times eventually return. The taxes, in turn, make it harder to attract private-sector jobs and to keep young new residents once they start families.

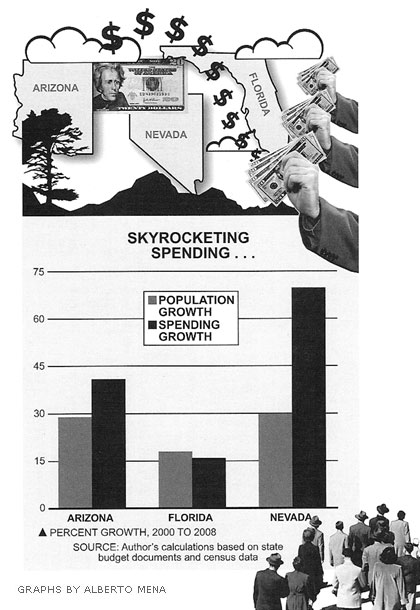

But in terms of flagrant profligacy during the good times, Arizona, Nevada, and Florida—those low-taxing, low-spending, every-man-for-himself states—have put New York and California to shame. Between 2000 and 2008, Arizona state spending (after inflation) grew by 41 percent, outpacing population growth by 12 percentage points. In Nevada, spending grew by 70 percent, outpacing population growth by 40 unbelievable percentage points. Only Florida managed to keep general spending growth roughly in line with population growth. But that state kept its population growth artificially high—and its spending growth artificially low—by using its state-guaranteed property-insurance program to subsidize torrid real-estate development in natural-disaster-prone areas where people otherwise would never have been able to afford to live. When disaster strikes, as it must, Florida—and the rest of us—could be on the line for billions of dollars.

Some of the states’ spending was the necessary consequence of rapid population growth. Take Queen Creek, where city officials had to build a “community from the ground up”—in the words of Mayor Art Sanders, himself a real-estate developer—including a lot of public-sector infrastructure. For example, Queen Creek homeowners formerly paid a private firefighting company for coverage. As the town expanded, however, it wanted to participate in a local program through which neighboring towns’ firefighters would help one another out. But a combination of state regulations and its own recalcitrance kept the firefighting firm from participating in the program, and it didn’t provide stellar service anyway, Sanders says. So Queen Creek created its own public fire department and funded it with a new property tax.

Similarly, the town has built a state-of-the-art library that looks more like a Barnes & Noble, where kids and adults take advantage of the late hours to read after work and school. Sanders doesn’t seem to prefer the public sector to the private sector for any particular task. But some basic service functions seem invariably to gravitate to the public sector, as the population evolves from a few farmers with their own informal network of services to individual homeowners, often from out of state, who expect the government to provide such services and much more.

Yet most of the three states’ dizzying spending isn’t the consequence of new public services required by new towns. It’s instead due to those culprits familiar to budget hawks on the East and West Coasts: education and health care. In Arizona, for example, education spending is up 32 percent in the past four years alone, outpacing the rest of the budget, says Byron Schlomach, director of the Center for Economic Prosperity at the Goldwater Institute. (Among other things, the spending pays for a new full-day kindergarten program for public school students.) Health care has more than held its own, too, as former governor Janet Napolitano tried diligently to expand Medicaid eligibility to middle-class families. Education spending in Nevada has more than doubled in real terms since 2000, also outpacing general spending, with hundreds of millions earmarked for class-size reduction.

With tax revenues plunging by double-digit percentages in all three states—nearly three times as fast as the national average, according to the Rockefeller Institute—all this spending has left budgets dangerously out of whack. Florida’s deficit is 23 percent of its general budget; Nevada’s and Arizona’s are more than 30 percent. In fact, Florida, one of only 11 states with a sterling AAA rating from Standard & Poor’s, is in danger of losing that rating.

Further, Arizona and Nevada, while ramping up spending, have failed to fund future pension liabilities—payments that they must make to future state retirees, so that they’re consistent with the national average. Arizona has funded only 79 percent of its future payments, while Nevada has funded 77 percent. (Florida, to its credit, has actually overfunded its plan.) True, these shortfalls aren’t huge compared with the 82 percent national average. But neither are they signs of fiscal stewardship, a particularly troubling fact in Nevada, where the number of state retirees has nearly doubled in the past decade.

The three states have faced wrenching debates about how to close this year’s budget gaps. Only Florida has passed a budget without new taxes. But it did so mostly with one-shot gimmicks that make future problems worse, like raiding a byzantine array of reserve trust funds. As the state’s budget hole gapes again, the legislature has floated the idea of new fees and a cigarette-tax hike, and even these steps may not be enough. Governor Charlie Crist, a Republican, has resisted new levies so far, but he’s almost out of one-shot budget tricks. That may be why he was one of the Republicans who adamantly supported President Obama’s health-and-education-heavy stimulus package. That money may save him from a massive tax increase—for now.

Nevada and Arizona, though, after modest budget cuts, are raising taxes with zeal. In mid-March, Nevada’s legislature hit its economy where it hurts, enacting a hotel-tax increase initially meant to raise nearly $300 million annually (plummeting tourism brought that projection down to $233 million). Republican governor Jim Gibbons has made a show of not endorsing the increase—but as the legislators who voted for it have grumbled, the hike was in his proposed budget, and it doesn’t require his signature to become law. Geoffrey Lawrence, a fiscal-policy analyst at the Nevada Policy Research Institute, worries that more new levies are coming and that the state is gearing up for a repeat of 2003, when it passed the biggest tax increase in state history. Once the economy started growing, Lawrence remembers, the state “used that money to expand programs.”

And in Arizona, new Republican governor Jan Brewer has proposed $1 billion in as-yet-vague tax hikes, including a possible boost in the sales tax. She has also floated the idea of permanently repealing a currently suspended state property tax sometime in the future—in exchange for a temporary return of the tax now. It’s a political convolution that would make New York Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver proud.

Why haven’t the JetBlue states reduced spending when faced with the downturn, instead of turning to new taxes? A big reason is the growing power of special interests that depend on taxpayer dollars, making these once-frugal states look a bit more like California and New York. Over the past decade, for instance, notes Lawrence, Nevada’s public employees have won jaw-dropping raises (more than 8 percent annually, in some cases) and now balk at giving any of them back—though county officials have had some success here. The Nevada teachers’ union spearheaded the recent hotel-tax hike, which includes a long-fused budget bomb: for the first two years, it will support general spending and close the deficit, but afterward it will support permanently higher teacher pay.

The special interests have become adept at weaving lavish spending deeply into state budgets in good times, so that it’s hard to cut when times get tight. In 2000, to take one example, Arizona approved a new sales tax, specifically for providing extra funding for education. Back then, with the economy booming, it didn’t seem like a big deal. But as revenue from the dedicated sales tax falls with the struggling economy, education advocates will complain and the state will be tempted to subsidize the shortfall with other taxes—turning a separate, dedicated tax into a more general claim on the state budget. In Florida, advocates want state funds to make up for education funding shortfalls at the county level, which would bring the state a step closer to New York’s ruinous arrangement: massive state subsidies for education, which encourage local governments to jack up their own spending, knowing that someone else will pay for it.

The political culture of the three states seems to be transforming, too, making them friendlier to the “spending lobby,” as Schlomach calls it. Arizona, the only one of the three states with an income tax, now seems to have plenty of supporters for raising that tax. One unscientific poll in the Arizona Daily Star found a majority of respondents in favor of such an increase, including an Albany-style tax hike on the “rich”—those making more than $150,000 annually. And Florida has seen Albany-style organized protests against even modest education cuts.

Both Lawrence and Schlomach believe that demography has a lot to do with this shift. “The biggest risk is Californians moving here,” says Schlomach. “They are fleeing California, but they don’t have any notion of why it’s expensive to live there.” They don’t realize that part of the reason it’s still “not super-expensive here” is the relatively small extent of government ser-vices, he adds. Echoes Lawrence: much of the population increase into Nevada is from California, and “they’re taking their voting culture with them.”

Besides immediate, massive budget deficits born of boom-era spending, the frontier states face additional challenges, familiar to residents of older states. One involves infrastructure reinvestment. When high-growth states invest in brand-new infrastructure, they can be confident that new tax revenues—from the new development that the infrastructure will support—will pay for it. But it’s another thing altogether to keep investing in the same old infrastructure just to maintain your current tax revenues and prevent your existing residents and businesses from fleeing, as states like New York and California must do.

For the first time, in many cases, the JetBlue states must do this work of reinvesting in aging infrastructure. The American Waterworks Association has said of Arizona’s vast water-infrastructure needs that the state now faces the “dawn of the replacement era.” The American Society of Civil Engineers said last year that “much of Florida’s flood-control infrastructure is reaching its life expectancy.” And all three states face massive transportation-investment decisions in the coming decades, as exurban traffic in far-flung developments worsens.

Another old-state problem that the three Sunbelt states must soon confront is social spending. Mass foreclosures are leaving neighborhoods vulnerable to lasting economic and social change. Robert Allen, an Arizonan who just last year turned what was a construction-support company into a business cleaning out foreclosed houses for banks and property managers, says that he’s already noticed a quality-of-life decline in some parts of Mesa and outlying suburbs. Mass foreclosures encourage vandalism and burglaries, and blight drives away potential newcomers; owner-occupied neighborhoods are turning into rentals. One police station in a foreclosure-wracked area of Gilbert, a bedroom community of Phoenix, has seen a 46 percent increase in calls, according to the Arizona Republic.

Most neighborhoods aren’t in such dire straits, thankfully. Some, in fact, are close-knit enough to guard empty houses themselves and pay the electricity bills to deter vandals. But foreclosures could still force the government to spend lots more on certain suburban neighborhoods, especially on policing—making them net consumers, not payers, of taxes.

For now, Nevada can still run full-page ads in California’s papers trumpeting its no-income-tax living. And Arizona’s freedom-loving culture suggests that it won’t be turning fully to Gotham-style big government any time soon. When I asked various people there how the government ought to help, nobody advocated mass-scale homeowner bailouts. Sanders, the mayor of Queen Creek, didn’t cry about foreclosures in his town, grumble about plummeting property-tax revenues, or ask for government money. Many Arizonans seem to have acquired a new understanding of how markets work, rather than a new distrust of them. As Marylee Bell, a Queen Creek restaurant owner, says, “It makes sense for people who overpaid to lose their homes and rent them back from people who didn’t.” (Bell’s idea for an improved economic bailout plan from the White House: “Cut taxes.”) Stories are also starting to emerge of people who just purchased a house for $189,000 that had sold two years ago for $425,000.

Further, Allen notes that many of his neighbors have started new businesses as the economy has stagnated. The long-booming construction industry, so reliant on independent contractors, encouraged a culture of self-employment. And more than a few people who caught the speculative fever in Arizona and Nevada have software or other professional backgrounds from California and elsewhere, meaning that they have the tools to start nonhousing businesses in their new home states.

Demographically, too, the frontier states’ future still seems fundamentally sound, if based less on scorching growth in people and property values. If the past 200 years are any guide, the nation will keep getting bigger, and people will still seek cheaper places to live, something that Arizona, Florida, and Nevada have on offer once again.

But the low-tax, low-services culture is up against a potent force: the inexorable mathematics of budgets that take on a life of their own once they’ve passed the point of no return. If the way that Arizona, Florida, and Nevada are confronting the current crisis is any guide, these states will continue to grow—but they will also grow a little bit more like us.