Socialized medicine’s finest hour arrived on October 16, 1975, by the marshes of Bhola Island off the coast of Bangladesh. There, in the frame of three-year-old Rahima Banu, the World Health Organization finally cornered smallpox, the most dreadful killer on the planet. Then as now, there was no known cure for the highly contagious smallpox, but vaccinating others on Bhola Island kept the virus from skipping to new human hosts, and little Rahima was the last one left.

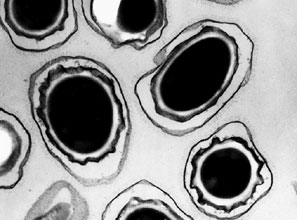

We have been slouching down the road to pharmaceutical serfdom ever since. Where that has left us will become clear one windless summer evening, when a low-flying Cessna scatters 200 pounds of anthrax over the rooftops of Manhattan from Harlem to Battery Park. Anthrax is the smallpox movie played in reverse. It isn’t very contagious at all, and its spores are ordinarily quite sticky and easily contained, but when deliberately coated with silica, they disperse like ragweed pollen in spring. They can thus be used to kill New York without endangering Islamabad. As the spores germinate, bacterial toxins drill through your flesh, gangrene sets in, organs collapse, lungs fill with fluid, and you die within a week. One Cessna’s worth could easily kill a million people. The threat, numerous intelligence assessments have concluded, is all too real.

If you spot the plane over Times Square tomorrow, prepare for a shot of Biothrax—a vaccine developed by the Pentagon in the 1950s—and prepare, too, for some side effects, unpleasant or possibly worse, that today’s drug designers could almost certainly eliminate. Or head for the hills, because the plane may instead be carrying Ebola or one of a fistful of other killers for which we have no antidotes at all, or perhaps smallpox or plague genetically rejiggered to evade the antidotes we’ve got. In today’s ongoing struggle between designed germs and designed drugs, we aren’t ready to defend ourselves against existing threats, and we aren’t going to close the microbial missile gap any time soon.

That should surprise many and will leave the rest of us feeling savagely wise. The germ-fighting end of the business is already pretty much where the health-care Left says the whole drug industry belongs, and has been for years. Drug companies supply what Washington requisitions, at prices dictated and quality minutely controlled by the one, omnipotent customer—if the right companies show up to supply it. But they no longer do. Even the smallpox story, it turns out, testifies to a decidedly unsocialist fact: we can’t defend ourselves against biological attacks without the private capital and expertise of a thriving, nimble, endlessly innovative civilian drug industry. We will all regret this together, because the spores, when they arrive, will dust and snuff Mayflower WASPs and rainbow immigrants, Lower East Side and Upper West Side, people of every party, hue, ethnicity, gender, lifestyle, and sexual orientation.

The government took control of germ-fighting bit by bit. The army began systematically vaccinating soldiers against smallpox during the War of 1812. During an 1815 epidemic, New York helped fund free vaccination for the poor, as did other cities and towns throughout the nineteenth century. Launched with the help of the man whose likeness now adorns the coin, the March of Dimes funded the development of Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine and oversaw the first large field trials. The Centers for Disease Control now buy over half of all vaccines used in the United States, and federal insurance programs cover another large chunk. In Washington, the government has taken the lead in isolating the new swine-flu virus, growing the seed stock needed to manufacture a vaccine, and setting aside funds to buy billions of doses.

Quality control slipped into Washington along with the money. In 1813, Washington appointed the army’s supplier to serve as the nation’s “vaccine agent,” in charge of providing “genuine vaccine matter” upon request. Enacted in 1902, the first federal drug-safety law established a national biologics lab to ensure that vaccines and a few other medicines culled from nature were “safe, pure, and potent.” Safety agencies got whacked for letting the bad slip through but not for impeding the good, so over time they grew increasingly cautious. A recently licensed vaccine—it protects against a common rotavirus that kills about 60 American children a year and hospitalizes 70,000—required ten years of development by academics, followed by another 16 years of tests involving 72,000 patients.

When things go wrong anyway, Washington has made sure that the drug company can still be blamed. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) controls the warnings supplied with every drug and, to avoid scaring patients off their medicines, forbids too much warning as strictly as too little. Too little, however, may still be a plaintiff’s central claim against a drugmaker in a subsequent lawsuit brought under state law, and often is. At the same time, state courts also routinely instruct juries that every shot or pill comes with an “implied warranty” promising things that drug companies know aren’t true and would vigorously disclaim if they could. One arm of government thus limits what drug companies may say, while another invites juries to read lies or broken promises into their silence.

A key precedent on implied warranties was set in California in 1958, after certain batches of Salk’s new polio vaccine paralyzed 200 people and killed ten. The Cutter Company had failed to kill all the virus used in their manufacture. But Cutter had followed the virus-killing protocol specified by the national biologics lab—a botched rewrite of the one successfully used by two other manufacturers during the field trials that got the vaccine licensed. No matter: a court ruled that Cutter had implicitly promised that the vaccine contained no live virus. Some years later, Albert Sabin deliberately used a live but weaker strain of the polio virus to create a somewhat riskier but more broadly effective vaccine. Washington understood the trade-offs, licensed Sabin’s vaccine anyway, promoted it in preference to Salk’s, and left juries free to conclude, as some soon did, that Sabin’s should never have been brought to market at all.

Insurers began to bail. When an alarming new swine flu surfaced in 1976, Washington placed a big order for vaccine, insurers refused to cover, and drug companies then refused to supply. So Washington wrote the coverage itself, fought claims for the next decade, and paid out 60 times its original estimates. With liability costs then threatening to shut down the rest of the vaccine industry, Washington created a national insurance program funded by a tax on every shot of children’s vaccines. (To collect from the Treasury, however, claimants must convince an expert panel, not a wacky jury.)

With Washington and the trial bar now in complete control of almost every aspect of the science, packaging, insurance, and price, manufacturers were left to curry political favor and chase the economies of scale involved in manufacturing huge quantities of a few dozen tried-and-true vaccines. All the smaller players dropped out. In 1957, five important vaccines were being supplied by 26 companies; by 2006, only four major companies were making any vaccines at all in the United States. More than half of the routine children’s vaccines now come from just one manufacturer; four others from just two. Three companies dominate the global market.

To which Washington may cogently reply that its embrace has worked wonders. America underwrote much of the global war on smallpox, helped saved hundreds of millions of lives worldwide, and now saves as much in a single month of medical costs thus avoided as it contributed to the entire campaign. Every dollar we still spend on polio vaccine saves about five times as much on direct medical and indirect societal costs. Measles immunization pays ten to one.

But these triumphs of socialized vaccination were made possible by vaccines developed before the government’s creeping takeover of the industry had made vaccines anathema to most of the smart money. Even smallpox, as we shall see, was beaten by a weapon more ingenious than anything ever imagined at Los Alamos, created in a way that only a wildly free and competitive market can create. With anthrax, we have yet to see who will win—the Cessna or the city.

Biothrax was developed in the 1950s, tested in a few textile workers, licensed by the biologics lab, and then manufactured by a facility nominally operated by the state of Michigan. But the lab’s authority and the licenses it had already issued were transferred to the FDA in 1972, soon after Washington had declared that no drug could be deemed safe and effective without extensive human trials first. That presented a problem. Tomorrow, we may have a million people exposed to anthrax, and ad hoc clinical testing will then get started on the double. But today, we have none.

So Washington dithered—for 30 years. An FDA panel reported that Biothrax was fine, but only for use in the “limited circumstances” of exposure in research labs and from the industrial handling of animal hair—goat hair especially. The agency invited public comment, then neglected to finalize the relicensing paperwork. The Pentagon Biothraxed about 150,000 men and women involved in the first Gulf War anyway. Some veterans blamed unexplained illnesses on the vaccine. The FDA suspended production at the Michigan facility. The facility was transferred to private investors with Pentagon connections. The White House said soldiers didn’t have to get shot until the FDA paperwork had been finalized. Lawyers representing unnamed military personnel asked the FDA to admit that it hadn’t been.

Then, in September and October 2001, letters containing anthrax spores were mailed to national news networks, several newspapers, and two U.S. senators. Of the 18 Americans known to have been infected by inhaling anthrax between 1900 and September 2001, 16 had died. Eleven more were now infected by the letter attacks. The six who surprised almost everyone by not dying owed their lives to several powerful antibiotics—most notably, Cipro.

But antibodies work even better than antibiotics, so with the challenge to the vaccine’s license still pending at the FDA, Biothrax was offered and administered to some Capitol Hill and postal employees. Congress leaped into action and enacted a sweeping new drug law—call it the “Cessna law”—for bioterror antidotes. Once a cabinet secretary declares a health emergency—no need to wait for the Cessna to arrive first, and the emergency may last forever—the FDA may license any drug or vaccine on the basis of whatever evidence the agency deems sufficient. No human trials are required. A “lower level of evidence” applies. “May be effective” is good enough, so long as the “known and potential” benefits appear to outweigh the risks. The decision may be made “within a matter of hours or days.” If the drug is also certified as an antiterror technology, any subsequent lawsuits must be filed against the government, not the manufacturer. A federal judge, not a jury, will decide the case, applying evenhanded rules that make plaintiffs’ lawyers weep. Awards are capped. No punitive damages may be awarded.

As the ink was drying on the new law, a federal judge agreed that Biothrax still lacked a valid ticket for treating inhaled anthrax. The FDA immediately issued one. Nothing doing, responded the judge—the agency had evaluated Biothrax versus goats but not Cessnas. So the Pentagon invoked the Cessna drug law, and in a classic passing of the buck, the FDA licensed Biothrax for use by any and all recipients, military or civilian, so long as they were designated, warned, shot, monitored, and tracked by the Pentagon. A while later, the FDA took care of the goat-not-Cessna problem, completed the paperwork, and gave Biothrax a regular ticket. But then it quietly issued another emergency-use license to bypass some inconvenient fine print in the license of an anti-anthrax antibiotic. At the same time, ever so quietly, blanket liability protection was also extended to all “activities related to developing, manufacturing, distributing, prescribing, dispensing, administering and using anthrax countermeasures in preparation for, and in response to, a potential anthrax attack.”

Congress neglected, however, to pass a law resurrecting our once-nimble private vaccine industry to supply us with better-than-Biothrax countermeasures. In the last decade, Washington has funded the development of at least three new bioengineered anthrax vaccines, signed up one tiny company to provide 75 million doses for almost $1 billion, canceled the contract for nonperformance a few years later, signed a $450 million stopgap contract for 19 million doses of Biothrax, and initiated another round of bidding for 25 million doses of a new and improved vaccine. The blueprints for the four anthrax vaccines have changed corporate hands four times. But nothing has quite worked out.

A buyer that buys all the product, writes the patent laws, issues the licenses, and leaves the field wide open to tort lawyers, too, can easily crush intellectual property, deter innovation, repel new capital, promote consolidation among suppliers, and erode market resilience—and with vaccines, that’s what Washington has done.

That we have had serious trouble dealing with something as familiar as the flu should horrify us. A new vaccine has to be developed at least once a year to keep pace with the fast-mutating virus, but that process is now technically routine. Ramping up mass production, however, hinges on skill and some degree of luck at the companies that cultivate the new virus in acres of live cells. Five years ago, just three companies controlled most of the skill, and one of them got unlucky. The United States was left unable to provide even the routine, seasonal flu shots needed by the elderly and health-care workers, and completely unable to address a pandemic, had one materialized.

The 2009 swine flu happens to be a rare, four-way remix of two pig strains, one bird, and one human. Even if it doesn’t prove as lethal as first feared, the next random rewrite of this distinctly new genetic code might well be. Different strains of other viruses readily remix their genes just as the flu does, and deliberate remixing by people can be far deadlier than random remixing by pigs. There’s a serious risk of theft of biological weapons already on ice in old Soviet facilities and U.S. labs. The top-notch biotech facilities now being built by Malaysia, Cuba, and at least a dozen other developing countries could readily be used to brew new ones. Germs engineered to track ethnic, racial, and geographic lines—a possibility anticipated by novelist Frank Herbert in The White Plague—are now quite plausible. As the brilliant founder of Sun Microsystems has observed, we confront here “a surprising and terrible empowerment of extreme individuals.”

In the right political environment, drug companies would be delighted to take them on—biological warfare just accelerates the endless chess game of life and commerce that keeps them profitable. Margins collapse when patents expire, so tomorrow’s profits always depend on taming the next shard of endlessly variable human chemistry, or beating nature’s next new pathogen.

But Washington no longer seems to discern much connection between profit and innovation. Cipro was already the world’s best-selling antibiotic, generating about $1 billion a year in sales, when Washington asked Bayer to get a good-for-anthrax clause added to the license. Cipro was profitable because it was still young enough to be under patent, and the Pentagon was interested because Cipro was probably still young enough to be out ahead of al-Qaida’s antibiotic-resistant anthrax. After the 2001 attacks, however, three manufacturers immediately offered to supply generic Cipro for 80 percent less than Bayer’s, Washington immediately threatened to let them, and Bayer ended up giving away 2 million tablets and providing another 100 million at a steep discount. Sanofi Aventis, one of the largest vaccine suppliers, was quicker on its political feet. It located a cache of smallpox vaccine in one of its old freezers and immediately donated it all to Washington.

This sounds cozy enough, but cozy doesn’t draw new talent and money into an industry. Daunting scientific and manufacturing challenges make failure the norm in this line of work, and taking them on makes sense only when occasional success is highly profitable. In its best years, Pfizer was grossing over $1 billion a month on Lipitor. Imagine Washington’s fury if a Pfizer vaccine began raking in that kind of money after anthrax made it to Carnegie Hall. Tiny drug companies dare to dabble in the game only because they don’t have hundreds of billions already invested in expertise, facilities, and licensed drugs that Washington can devalue if displeased. But that’s also why the tiny can’t deliver.

That leaves the shadow customers—New Yorkers, for example—in serious trouble. The old smallpox was tough enough. Beating tomorrow’s will require every scrap of ingenuity, capital, and staying power that a vast civilian drug market can muster. Smart bombs owe their astounding agility to the same digital technologies that started out in garages, ended up in billions of laptops and iPods, and are affordable because massive civilian demand has made them as cheap as bullets. Drug economics work much the same way—drugs are indeed the next-generation information technologies, software encoded in carbon rather than silicon. The weapons that will win the wars of the information age will be supplied by free minds and markets. Socialized medicine doesn’t know where to start and will never keep pace.

But what about smallpox, socialized medicine’s greatest triumph? At the height of the Cold War, the Soviet Union and the United States joined forces under the aegis of a UN affiliate, bought billions of doses of vaccine, deployed tens of thousands of workers, mobilized national armies to isolate infected regions, prohibited public meetings, quarantined hotels and apartment buildings, dispatched helicopters, airlifted refrigerators, doctors, and nurses, established rings of immunity around newly infected areas, and then tightened the rings until only one ring surrounding one little girl was left; and she, standing tiny and tall, finished off the virus on her own.

The familiar story of the vaccine’s origins surely still warms every left-leaning political heart as well. On May 14, 1796, Edward Jenner injects eight-year-old James Phipps with cowpox pus taken from lesions on the hand of milkmaid Sarah Nelmes, and finds that this mild infection protects Phipps from deliberate attempts to infect him with an aged and thus weakened form of the human pox. Jenner publishes his findings two years later, content to gift the most valuable pharmaceutical discovery of all time to suffering humanity. “Yours is the comfortable reflection that mankind can never forget that you have lived,” writes Thomas Jefferson in a letter sent to Jenner in 1806.

But smallpox fought back. The strain that emerged 3,000 years ago killed about 30 percent of those infected. In the late nineteenth century, a milder strain appeared, killing a mere 1 percent. A 12 percent killer emerged in 1963. The first and worst perished on Bhola Island in 1975, but wiping out its siblings took another two years. To this day, as David Koplow recounts in his 2003 book Smallpox, “no one knows for certain where, when, or how these less noxious smallpox relatives crept into existence.”

We do know, however, that the vaccine that ended up beating them all wasn’t Jenner’s. The details are forever hidden, and Koplow himself doesn’t speculate about them, but it’s easy to surmise how this vaccine came into being. Picture how the market for what began as Jenner’s vaccine operated through all but the last few decades of its two-century run. Infectious muck was scraped from scabs found on cows or milkmaids, then scraped back into human arms. It was transported on sailing ships to America by moving it from arm to arm, a human chain letter. Unwashed human hands, knives, and needles did the scraping, inevitably picking up more muck along the way, including smallpox itself. Countless unregulated purveyors of vaccine got involved, many of them careless, incompetent, or worse. Washington did its bit here, too—the national “vaccine agent” it appointed in 1813 accidentally sent real smallpox instead of vaccine to North Carolina, infecting 60 people and killing ten.

But people apparently noticed and spread the word: this shot works better than that one. Such choices, accumulating over the years, had bred better grains, dogs, and sheep, and now they set about breeding a better vaccine. And on it went, until the huge Wyeth Labs picked what it considered the best of the breed, got it licensed, and—with a little help from the Left—obliterated the greatest bioterrorist of them all.

The story of Variola major ended in 1975, but vaccinia’s didn’t end until gene sequencers set out a quarter-century later to find out what it really was. The several strains of smallpox in the wild, we now know, were all eradicated by just one virus—the same “novel, separate creature”—in all the needles. It appears to be a remix of cowpox, another cousin that poxes horses, and the human pox. It was created, as Koplow notes, by means that were “somehow inadvertent, invisible to the practitioners, and global.” Or as a biologist and an economist whose lives overlapped Jenner’s might have put it, by means of natural selection and the invisible hand.

We don’t breed and peddle vaccines that way any more—we hardly breed and peddle any new ones at all. Our top priority, it seems, is to do to the rest of the pharmacy what we’ve done to vaccines. We should be undoing instead. No, we don’t want to reset the policy clock to 1800. But 1950 does merit a close look, because back then, companies and capital were pouring into the germ-killing market, new vaccines and antibiotics were pouring out, and both were regulated roughly as the Cessna law now once again provides for just a few.

A leap back to the pharmaceutical future might also help save the life of the patient who was dusted years ago with genes for Huntington’s disease, cystic fibrosis, or multiple sclerosis, and who now lies in the Mount Sinai Medical Center beyond help from any licensed drug. For him, the emergency is already as real and immediate as can be. And it is only by clearing for action at Mount Sinai today that we will develop the resources to protect Carnegie Hall and the rest of New York tomorrow.

Top Photo by Anthrax Vaccine Immunization Program/Getty Images